|

a

woman's

life

births

weddings

divorces

death

& dying

manners

cooking

housework

shopping

gardening

livestock &

poultry care

education

employment

opportunities

recreation

& hobbies

holidays

&

feast days

board

games

music

embroidery

& needlework

pet

keeping

reading

dancing

horseriding

hawking

hunting

sex &

sexual health

PLEASE NOTE!

ADULT THEMES!

|

Manners

For The Well-bred Medieval Woman

MANNERS - ETIQUETTE - CONVERSDATION - DEPORTMENT

- DRESSING APPROPRIATELY

ACCEPTING GIFTS - TABLE MANNERS - RULES FOR THE TABLE

Medieval manners

Manners

were a very important part of a medieval woman's life. The common

misconception of a rough and rude society with little polish is

a widely-mistaken belief. Manners

were a very important part of a medieval woman's life. The common

misconception of a rough and rude society with little polish is

a widely-mistaken belief.

It is true that medieval life could be violent and dangerous,

but people from all walks of life were bound to adhere to a certain

amount of daily courtesy. To fail to do so was social peril and

could cost a person their life for an insult, whether real or

perceived, against a person of higher social standing.

The late medieval poem, How

The Good Wife Taught Her Daughter gives motherly advice for

general deportment in public:

And when thou goest

on thy way,

Go thou not too fast,

Brandish not with thy head,

Nor with thy shoulders cast,

Have not too many words,

From swearing keep aloof.

For all such manners

Come to an evil proof.

Social

etiquette for the well-bred woman

Social standing and ones place in society was everything

in the medieval world. One might hope to advance through material

gains, but had little hope to do so without the correct courtesy

and manners.

Guibert de Nogent, c. 1055

– 1124) was a 12th century Benedictine who write extensively

on history and theology. He wrote about the decline in good manners

in women i his society:

"Alas, how miserably...

maidenly modesty and honour have fallen off, and the mother's

guardianship hath decayed both in appearance and fact, so that

in all their behavious nothing can be noted but unseemly mirth,

wherin are no sounds but of jest, with winking eyes, and babbling

tongues, and wanton gait, and most ridiculous manners.

The quality of their

garments is so unlike to the frugality of the past that in the

widening of their sleeves, the tightening of their bodiecs,

their shoes of cordovan morocco with twisted beaks- nay, in

their whole person, we may see how shame is cast aside."

A woman was always expected

to be the epitome of good manners no matter what her status in

life and the higher a woman was born, the more essential it was

for her to act appropriately.

Conversation

and speech

Manners which were appropriate for a man were not always appropriate

for a woman. Indeed, it was completely unseemly that a woman swear

for any reason whatsoever. Common women might, but it wasn't good

breeding. It would bring great shame upon her father or husband.

The medieval writer, Robert of Blois, admitted that ladies needed

to know how to behave, but that it was difficult for women-

"If she speaks,

someone says it is too much. If she is silent, she is reproached

for not knowing how to greet people. If she is friendly and

courteous, someone pretends it is for love. If on the other

hand, she does not put on a bright face, she passes for being

too proud."

A woman who entered a conversation

with a stranger might gain herself a bad reputation for being

too free and easy with stranger men and to accept a kiss from

a male friend or acquaintance or from a man who is not related

by blood or marriage, even on the cheek, would have had tongues

wagging and ruined a woman's reputation.

In

the middle ages, a woman's reputation was everything. Should there

be any kind of a legal dispute, or she be a witness in a counrt

case, her good moral reputation would assist in her being taken

seriously, not an easy task at best. In cases of sexual assault,

a spotless character was more likely (but not always) to get a

prosecution. In

the middle ages, a woman's reputation was everything. Should there

be any kind of a legal dispute, or she be a witness in a counrt

case, her good moral reputation would assist in her being taken

seriously, not an easy task at best. In cases of sexual assault,

a spotless character was more likely (but not always) to get a

prosecution.

When it came to chatting

with others, one should never address a social superior first,

especially if one was a woman, and an appropriate greeting must

be given. It was considered the height of rudeness to avert your

gaze to a man or woman who ranked higher than oneself. Honesty

was judged by the directness in the eyes and to hide ones face

was interpreted as dishonesty and ill-intent.

It was also incredibly rude for a woman to turn her back on a

social superior. She should wait for the person to pass or have

removed herself from the room backwards.

When introducing a person,

should there have been no man to do it for her, convention dictated

that a woman must introduce the highest rank to the lowest and

then vice versa. This is still true for introductions today.

An error in the order of introduction could have been a grave

insult indeed. Should a woman have found herself in the company

of important people and another important one arrive, she must

bow and move away to permit the newcomer the privilege of standing

closer.

When a woman entered the house or room of a person of equal standing,

a woman ought bow just a little to acknowledge the arrival. If

of higher standing, she ought kneel on the right knee. Should

she have been presented to the Queen, she knelt at the door, entered

only halfway and knelt again. Only if she was motioned further

might she have gone closer.

It was always better to err on the side of caution in this regard

as it was better to appear humble and meek than ill-mannered and

rude.

Deportment

Women were instructed to be gracious in their deporture and not

wriggle their shoulders, looking straight ahead with a tranquil

and measured air. When out in society, is was important that a

woman's hands not be touched by a man who is not of her family.

Public displays of affection in the form of hand-holding was quite

inappropriate.

Robert de Blois also wrote that

"Ladies should

walk erect, with dignity, neither trotting nor running, nor

dallying either, with their eyes fixed on the ground ahead

of them. They were to be particularly careful that they do

not regard men as the sparrowhawk does the lark."

When traveling outside the home, it was acceptable for any woman

to walk arm in arm with her female companion or a male member

of her family. A woman of good breeding did not venture out alone.

A working woman or a mother in a small peasant household may have

cause to go out alone, but only when unavoidable. Where possible,

she would send a son on an errand on her behalf or seek the security

of another woman's company when going to the bakehouse or to the

creek for washing. There's safety in numbers, and numerous court

cases exist where women were molested whilst out doing daily chores

in lonely places. Or at home. Or on the roads.

Dressing

appropriately Dressing

appropriately

Hair was almost certainly to be covered in one of the latest fashions

outside the house. For a great deal of the medieval period, to

go out with a bare head when one was not a child, could have a

woman marked as a prostitute or a women of dubious morals. In

Italy, this fashion was abandoned earlier than England and other

parts of Europe as Italians embraced elaborate braided hairstyles.

Unless one was a washerwoman or a engaged in manual labour, arms

were never bare.  If

a gown with wide sleeves was worn, then another with close fitted

sleeves was worn under it to cover the arms. If

a gown with wide sleeves was worn, then another with close fitted

sleeves was worn under it to cover the arms.

Chemise sleeves were never

seen in public. Only if the pin-on sleeves had been removed for

manual tasks might they be visible, but a women never left the

house or would recieve company without first covering her underwear.

The exception might be farm workers with short-sleeved kirtles

on a hot summer's day, as seen in the image at the right, from

the Tres Huers du Duk du Berry, early 15th century.

At certain times, the fashion for lower cut gowns were popular.

Of course, one who wore her dress too low-cut was again marked

for comment and gossip. It was assertained that a woman's neckline

may be low, as low as her armpits, but no lower.

Until the renaissance and Italian fashions took hold, the chemise

or smock was an undergarment, meaning that it shouldn't be seen

at all, except as we have previously mentioned. A good general

rule of thumb was that the under layer was covered by the next:

the chemise was covered by the kirtle, the kirtle by the surcote.

One would not expect to find a visible chemise under a kirtle

neckline or a kirtle neckline under a surcote.

Accepting

gifts from men

The Medieval Art of Love by Michael Camille tells us a

little about love's gifts, what may and may not be freely given

to a lady without being inappropriate.

He

tells us of a text by Andreas Capellanus which states- He

tells us of a text by Andreas Capellanus which states-

"A lover may freely

accept from her beloved these things- a handkerchief, a hairband,

a circlet of gold or silver, a brooch for the breast, a mirror,

a belt, a purse, a lace for clothes, a comb, cuffs, gloves,

a ring, a little box of scent, a portrait, toiletries, little

vases, trays, a standard as a keepsake of the lover, and so

to speak more generally, a woman may accept from her love whatever

gift may be useful in the care of her person, or may look charming,

or may remind her of her lover, providing, however, that in

accepting the gift it is clear that she is acting quite without

avarice."

This also gives us an insight

into what kinds of items were freely available at that time.

Medieval

Table Manners Medieval

Table Manners

Medieval people were very religious and prayer was an integral

part of the day. A prayer would certainly always be said before

any meal even when eating at home.

Hands were always washed both before and after a meal. Even people

with little in the way of tableware were conscious of basic hygiene

and good manners. Mothers have, after all, changed very little

over the course of time and always sought to instill the best

manners she can in her offspring. There is little hope of social

improvement with no manners and should one be called upon to serve

a person of higher rank, and it was imperative that offense not

be given, even unintentionally.

A feast would begin by less important people washing their hands

before going to the table. To fail to do so was the height of

rudeness. The upper class and guests of honour would be seated

by a servant. A washing bowl would be delivered to them at the

high table.

The chaplain would say a prayer before any of the food is brought

to the tables. Communal plates were usual and meant to serve four

people at once. The guests at the high table, however, only had

to share with one other person.

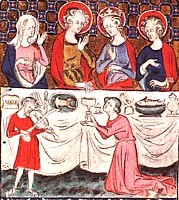

The

image at right shows a scene from the Duk du Berry's Tres Riches

Heures, illuminated 1412-1416. Food and fine clothing show

a standard of living above the average man. The

image at right shows a scene from the Duk du Berry's Tres Riches

Heures, illuminated 1412-1416. Food and fine clothing show

a standard of living above the average man.

The Roman de la Rose, a famous French poem from the 13th

century, gives advice to a woman in her table manners:

"She ought also

to behave properly at table. She must be very careful not to

dip her fingers in the sauce up to the knuckles, nor to smear

her lips with soup or garlic or fat meat, nor to take too many

pieces or too large a piece and put them in her mouth.

She must hold the morsel with the tips of her fingers and dip

it into the sauce, whether it be thick, thin, or clear, then

convey the mouthful with care, so that no drop of soup or sauce

or pepper falls on to her chest.

When drinking, she should exercise such care that not a drop

is spilled upon her, for anyone who saw that happen might think

her very rude and coarse. And she must be sure never to touch

her goblet when there is anything in her mouth. Let her wipe

her mouth so clean that no grease is allowed to remain upon

it, at least not upon her upper lip, for when grease is left

on the upper lip, globules appear in the wine, which is neither

pretty nor nice."

Medieval manners for the table

- Persons of lower rank

stand upon the head of the house and important guests entering

or leaving the room

- One uses one's own knife which was brought with oneself.

- Forks were cooking utensils. Never eat with them.

- Food is picked up by stabbing with the knife but NEVER did

the knife go to the mouth.

- The food must be removed fromt he knife with the fingertips

to eat.

- Do not make many selections and gather them to your plate.

- Keep your elbows off the table while eating.

- Do not belch or spit at the table.

- Do not stuff your mouth full.

- Do not dip meat or fingers directly into the salt bowl. Use

the knife tip.

- Do not leave a spoon in a dish when you were finished.

- Do not use the knife to pick your teeth.

- Do not take all the choicest morsels for yourself.

- Meat should be cut from the joint.

- Bread should be cut, not broken and the upper crust offered

to the guest.

- It is acceptable to select fruits, tarts and morsels with

one's fingers.

- A spoon should be used for broth. Do not lift the plate to

your mouth.

- Under no circumstances eat the trencher (plate of stale bread).

- Napkins to be placed over the left shoulder or left wrist

and used.

- Do not wipe your mouth on your sleeve- use a napkin.

- Take a cup with both hands to drink if it is shared.

- Wipe your mouth on a napkin before drinking from a shared

vessel.

- If you are offered a drink from the host's cup, do not pass

the cup around.

Copyright

© Rosalie Gilbert

All text & photographs within this site are the property of

Rosalie Gilbert unless stated.

Art & artifact images remain the property of the owner.

Images and text may not be copied and used without permission.

|