|

beauty,

health &

hygiene

general

healthcare

skincare

cosmetics

& perfumes

body

hair

cleanliness

& hygiene tools

bathing

hair

care

hair

styles

oral

care

& dentistry

intimate

feminine

hygiene

|

Medieval

Feminine Hygiene

* adult themes *

MENSTRUATION - PREMENSTRUAL TENSION - THE WANDERING

WOMB - FEMININE HYGIENE PRODUCTS

Menstruation

Surprisingly, we do know a little about that certain time of the

month thanks to medical treatices like those attributed to Trotula.

An English copy from the early 15th century advises that:

Women have purgations

from the time of twelve winters to the time of 50 winters,

although some women have it longer, especially those with

a high complexion who are well-nourished with hot meats and

hot drinks and live very much in leisure.

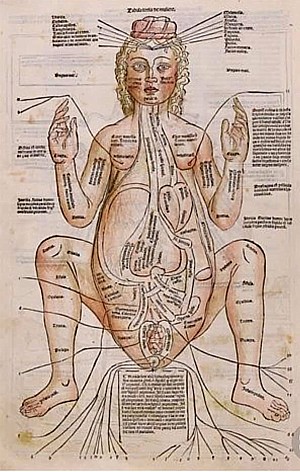

The image above shows a woman

in the setting of the zodiac with her menses flowing out of her,

and holding in her hands what might be an extremely crude astrolabe

for nagivating the heavens or her feminine hygiene product for

navigating her monthly cycle.

It is unlikely that the fluid flowing from her body is urine,

as in matters of urinary health, medieval imagery constantly shows

the patient or doctor holding a urine flask, which this is visibly

not.

Punishment

from God

Some

doctors called menstruation a sickness although it was generally

agreed by most that it was a punishment from God. Women needed

to pay for Eve's original sin in the Garden of Eden and menstruation

was therefore deserved, part of God's plan and not in any way

in need of medical intervention. Some

doctors called menstruation a sickness although it was generally

agreed by most that it was a punishment from God. Women needed

to pay for Eve's original sin in the Garden of Eden and menstruation

was therefore deserved, part of God's plan and not in any way

in need of medical intervention.

If a woman suffered with cramps or excessive flow, it was because

God willed it. It was also seen as extremely significant that

holy women were often found to not menstruate, thus substantiating

the belief of regular women were sinners who deserved their lot.

In reality, the extremely

frugal diets of very pious women were probably the underlying

cause for the lack of menses. With a strict monastic diet and

lack of proper nourishment, the body could not longer sustain

a pregnancy or reproduce and the menses stopped. If a woman left

the harsh religious life and returned to the secular world and

diet, her menses would return.

Again, this was seen as an undisputed sign from God of the holiness

of nuns and the worldliness of other women generally. Another

possible reason for the lack of menses in holy women is that many

wealthy women only turned to a life of religious contemplation

very late in life and were possibly post-menopausal.

Either way, troubles associated with menstruation were seen to

be something that was not in need of any medical intervention.

To do so, was to place your own ideas above those which God had

planned for you, and that was a bit risky. Nevertheless, medieval

medicine offered herbal relief for painful periods.

The Tacuinim Sanitatus, Vienna,

also known as The Four Seasons of the House of Cerruti, offers

this advice:

Parsley: It is good

for the health because it unblocks occlusions, helps the bladder

to function properly and relieves the discomfort of the female

period. It heats the blood and excessive use also causes headaches.

Medical

beliefs Medical

beliefs

Those who were more medically minded believed that the menses

bloodletting started at the head and traveled throughout the body

collecting poisonous wastes and humors. This was because most

medically minded doctors believed in the Theory of the Wandering

Womb.

This particular theory was the cause for any number of female

illnesses.

The

theory of the wandering womb

Medical practitioners during the middle ages failed to agree on

a rather unusual point connected to feminine complaints- whether

the womb was stationary or whether it wandered around inside the

body causing a variety of other ailments- including vomiting if

it stopped at the heart, and loss of voice and an ashen complexion

if it stopped at the liver.

The stress of a wandering womb was usually believed to be the

cause of hysteria. Indeed the word hysterical translates loosely

as madness of the womb. Even physicians who did not adhere

to the theory of the wandering womb, agreed that hysteria was

a solely female complaint and was probably caused by a lack of

intercourse when uterine secretions built up and were not released,

thereby causing the entire body to be poisoned.

Popular

menstruation beliefs

There were a lot of what we consider today, to be ridiculous beliefs

attached to medieval women and menstruation in the middle ages.

One popular belief was that sex with a menstruating woman would

kill or mutilate the semen and produce horribly deformed offspring

or children with red hair or leprosy.

Just the gaze of an old woman who still had her periods was thought

to be poisonous- the vapours being emitted from her eyes. It was

also believed by some that the touch of a menstruating woman would

cause a plant to die- a belief which was probably not shared by

landowners who required women to work alongside men in the garden

and would not have wished to lose days of productivity each month.

The Four Seasons of the House of Cerruti, a copy of the Tacuinum

sanitatus, assures women that their gaze while menstruating will

kill, quite specifically, pumpkins:

Take care that women

do not come near because if they touch the pumpkins, they

will prevent them from growing; they should not even look

at them if it is the time of their periods.

Pliny the Elder, in the first

century, declared that the menstrual fluid was most potent-

Contact with it turns

new wine sour, crops touched by it become barren, grafts die,

seeds in gardens dry up, the fruit of the trees fall off,

the bright surface of mirrors in which it is merely reflected

is dimmed, the edge of steel and the gleam of ivory are dulled,

hives of bees die, even bronze and iron are at once seized

by rust, and a horrible smell fills the air; to taste it drives

dogs mad and infects their bites with incurable poison.

Pliny reported that the poisonous

properties of menstruating women could be put to good use. If

menstruating women go round the cornfield naked, it would act

as a powerful insecticide, he wrote. Caterpillars, worms, beetles

and other vermin were expected to be eliminated. During plagues

of insects, Pliny had read, menstruating women had been instructed

to walk around the fields with their clothes pulled up above their

buttocks. He does not note whether this proved a successful remedy

or not.

Premenstrual

Tension Premenstrual

Tension

As with our modern society, premenstrual tension was not undiagnosed.

Known as melancholia, very little effort was spent in

seeking causes or cures as it was once again seen as God's natural

design for the female and therefore not necessary of change.

In spite of this, many herbal remedies were widely known and

used by medics who claimed that for every ill and suffering

that God causes, so he also provides the cure in the natural

world, and these were provided by God for our use.

Many herbal remedies, therefore

might be utlisied.

The astringent leaves of Lady's Mantle, Alchemilla vulgaris,

at left, were helpful with profuse menstruation.

Thyme,

Thymus species, was used for 'women's complaints' and as

an ointment for skin troubles. Thyme,

Thymus species, was used for 'women's complaints' and as

an ointment for skin troubles.

Fresh leaves of Woodruff, Asperula odorata, (shown at

right) made into tea and drunk was recommended for nausea.

Aldobrandino of Siena produced

a work Regime du Corps which included advice on feminine

hygiene, skincare and gynecology.

According to the 14th century manuscript, Tacuinum Sanitatis,

fennel was particularly useful for menstruation. It also advises

that acorns would prevent menstruation from occurring, but does

not indicate how the acorns should be eaten. It goes on to say

that this could be countered by having the acorns roasted with

sugar.

Feminine

hygiene products- the options

Free

bleeding

I have seen any number of social media posts claiming that medieval

women just bled into their clothes or bled into their red, linen

petticoats or chemises. That's a myth. The idea may seem sound

on the surface, but a look at what we know about medieval clothing

seems to disprove this.

Firstly, medieval clothes

were expensive and hand made. The poorer a person was, the more

their clothes needed to last and were of value to them. The

higher up a lady was, the more expersive her brocaded silks

and cut velvets were. Allowing staining and smell to permeate

the fabric time and time again, month after month seems to not

sit well with the idea of looking after their clothes.

Red, linen underclothes

to disguise the stains also falls apart as a theory. Chemises

weren't red. Undergowns might be, but the linen chemises under

them were not. A huge body of evidence points to white underclothes

or perhaps naturally bleached linen for the lower classes. Red

dye was extremely expensive. Wasting it on clothing that wasn't

seen just wasn't done. And then there's the problem that linen

doesn't hold red dye very well at all. It washes out fairly

quickly which would leave a pale, pink linen chemise- not substantiated

in either art or literature or particularly helpful in disguising

blood stains.

As a theory, it just doesn't

work.

Tampons

There is very little information about what was used for a woman's

monthly period written. Trotula mentions wads of cotton being

used for the cleansing of the inner canals of the woman's vulva

prior to sexual intercourse with her husband, but it is unlikely

that a similar cotton wadding may have been used for a kind

of medieval tampon as the belief in letting the menses flow

and drain from the body prevailed.

Certainly tampons were

known and used for keeping medicines in their proper place for

ailments of a woman's privvy place, but should we then conclude

that tampons were used for periods? No. To plug up the flow

of menstrual blood would be seen as both dangerous and injurious

to the woman when the blood was known to be extremely toxic.

Pads,

sheets, rags and clouts

Obviously, some device was necessary, so this leaves the alternate

as a stuffed sanitary pad or napkin of some kind as a logical

conclusion.

Historian Rachael Case

has discovered a written reference to period supplies, linen

sheets, in the Sumpturay laws for the Nunnery at Sonneburg.

Bishop Nicolaus of Cusanus wrote:

... each and every

one is to be given a chorkutte (frock to wear in church),

a frock for the day, a long fur (coat), a Kursten (fur frock

or gown), two night gowns, a scapular for the day, a scapular

for the night, veils and kerchiefs as they need; and if

they have the female sickness, they need linen shirts and

linen sheets as long as the sickness lasts. They may have

bedclothes according to the rule and customs of the order...

The size of these linen

sheets is not specified, but I feel these were less bed-sheets

and more small, folded sheets of linen like a sanitary napkin.

My own thoughts turn to the stuffed pads we have available today

and consider what might have been available to the medieval

women.

A stuffed pad of linen

fabric seems extremely possible, but when filled with linen

wadding would make a pad which would be unlikely to launder

well for reuse. A single sheet of linen folded repeatedly which

unfolded for laundering might be quite workable, but a pad with

linen filling would probably not wash well and dry badly in

the winters. Since the lower classes also menstruate, it seems

that when considering a reusable, washable pad, this was not

the answer. It seems that due to wool's water-dispelling qualities,

it is also an unlikely stuffing for a sanitary pad.

In

the middle ages, sphagnum moss, Sphagnum cymbifolium,

shown at right, was used for toilet paper and was also believed

by surgeons to have antiseptic properties. In

the middle ages, sphagnum moss, Sphagnum cymbifolium,

shown at right, was used for toilet paper and was also believed

by surgeons to have antiseptic properties.

It was also known by the name Blood Moss and was used during

the crusades by physicians to stem blood flow in battle wounds.

It was renown for its sponge-like absorbent qualities and ability

to be rinsed out and reused. A Gaelic Chronicle of 1014 relates

that the wounded in the battle of Clontarf stuffed their

wounds with moss, and the Highlanders after Flodden tended

to their bleeding wounds by filling them with bog moss.

It occurs to me that this

might make an exceptionally good filling for a sanitary pad-

absorbent, reusable, washable, almost instantly driable and

freely available to both wealthy and the lower classes alike

in almost all geographic locations. The benefit of antiseptic

properties from a woman's poisonous menstrual blood would possibly

be seen as an added bonus.

Although there is no concrete

proof, it is entirely possible that medieval women used moss-stuffed

napkins as sanitary pads. We know that moss is very like a very

fine sponge. It easily and quickly absorbs liquid and retains

it. Water can be squeezed out and the moss does not collapse

and is ready for reuse. A pad of sphagnum moss would absorb

the blood in lateral directions well as above and retain it

until fully saturated.

In a forum discussion in

January, 2006, Robin Netherton discusses an interesting find

from a burial at Herjofsnes. It concerns a pad, possibly used

for incontinence. It is made of sealskin, wool and has traces

of moss in the filling. Her conclusions are:

When the body was

laid in the grave there must have been lying on the back

of os coccygis ... a strip of sealskin to which was fastened

a redbrown woolen cord to keep the sealskin in place, while

in front on mons pubis it was also kept in place by a couple

of woollen cords which probably passed up to a cord or belt

about the hip-region, thus representing a kind of bandage

passing from mons pubis between femora down before pudenda

and anus and up between nates in the sacral region.

It shows that the possible

use of a pad for both incontinence and other bodily fluids was

known. Indeed, before the advent of the self-adhesive sanitary

pad, napkins were similarly suspended, although from modern

elasticised suspenders.

Copyright

© Rosalie Gilbert

All text & photographs within this site are the property

of Rosalie Gilbert unless stated.

Art & artifact images remain the property of the owner.

Images and text may not be copied and used without permission.

|